January 10, 2017. The Columbus Dispatch.

A growing number of cities have adopted local IDs as a way to help vulnerable people — domestic-violence victims, ex-cons, foster teens, low-income seniors, the homeless, transgender adults or undocumented immigrants — who sometimes have difficulty obtaining a traditional ID.

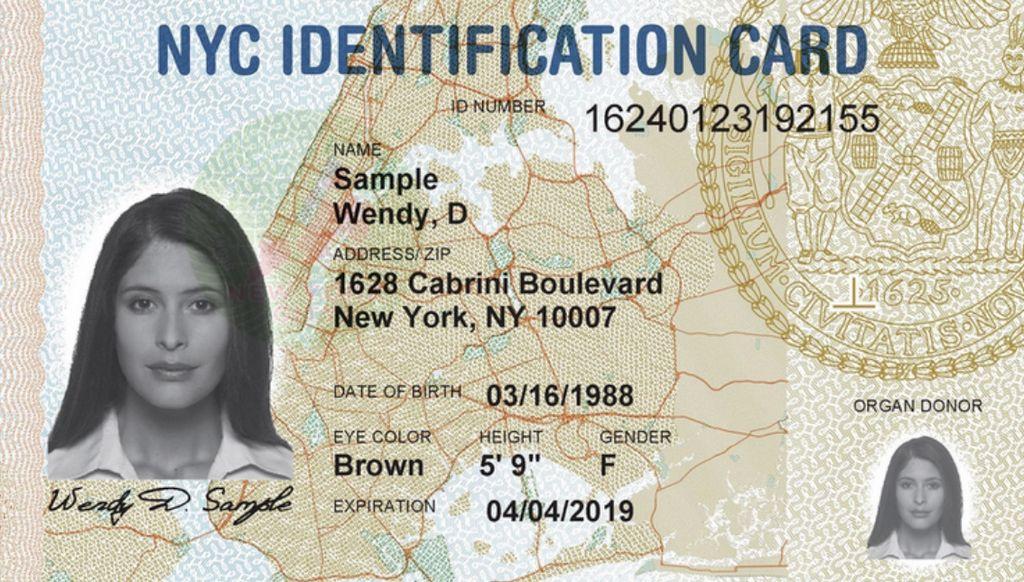

Imagine having a card that would prove your identity and residency, plus give you access to city services, business discounts and memberships to museums and other venues.

That’s the idea behind a proposal by a coalition of faith leaders and social-welfare groups that wants Columbus City Council to adopt a municipal ID card.

“The notion of having just one ID says it all,” said Gloria Phillips, a member of BREAD, which has been mobilizing congregations of a variety of faiths on social-justice issues like this for years. “Ideally, the card would be for everyone to be used everywhere.”

A growing number of cities have adopted local IDs as a way to help vulnerable people — domestic-violence victims, ex-cons, foster teens, low-income seniors, the homeless, transgender adults or undocumented immigrants — who sometimes have difficulty obtaining a traditional ID.

An estimated 11 percent of adult U.S. citizens don’t have a government-issued ID, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law.

Without proper documentation, individuals often can’t borrow books from local libraries, enter government buildings, file police complaints, open bank accounts or sign up for a food pantry.

“Not having a valid ID forces many people to live in the shadows,” said Tom Gearhart, a member of One ID Columbus, a coalition of faith leaders, homeless advocates, labor unions and worker groups that has joined BREAD in this effort.

People who don’t have identification are also often reluctant to report abuse, crimes or other violations such as landlord or workplace disputes, even when they are the victims, added Ed Hoffman, another One ID Columbus member.

Officials in New Haven, Connecticut, rolled out the first program in 2007 in response to attacks on immigrant and low-income residents, who sometimes carry large amounts of cash because they don’t have bank accounts.

Since then, a number of other cities — including Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, New York, Oakland and San Francisco — have taken the step, Gearhart said. More are considering it, with each city taking its own approach.

Some are focused on providing basic IDs for vulnerable populations, while others have tried to broaden the cards’ appeal by offering amenities such as debit-card features or discounts to cultural institutions and entertainment.

Columbus advocates are most heartened by the success of the New York cards, which are in the wallets of 900,000 — or one in 10 — New Yorkers.

A previous effort by BREAD — short for Building Responsibility, Equality and Dignity — to get Columbus law enforcement and city departments to accept identification cards for Mexican nationals — cards called matricula consulares — never got off the ground.

The issue of cards should be addressed as part of national immigration reform, said Robin Davis, spokeswoman for Mayor Andrew J. Ginther.

She also questioned the newly proposed card’s limitations and costs.

The cards wouldn’t replace driver’s licenses and couldn’t be used for boarding commercial airlines or signing up for public-assistance benefits or other services that require a driver’s license, critics said. Based on the experience of similarly sized cities, startup costs could run upwards of $1 million.

Others worry that the card wouldn’t be the solution that some hope it would.

“It doesn’t do anything to help homeless people get a job, an apartment or vote,” said Donald Strasser, a board member with the Columbus Coalition for the Homeless.

Still, backers say, the card “can’t hurt” and might offer other benefits that people who are living in shelters, on friend’s couches or on the streets might want. “These are good people working on this, and we support them,” Strasser said.

Columbus Councilman Michael Stinziano is so intrigued by the idea that he plans to hold several public meetings on the proposal, including one at 1:45 p.m. Sunday at Christ the King Church, 2777 E. Livingston Ave.

“I’m very interested in hearing more, and do feel there’s a value,” he said.

View original article.