By Hannah Phillips, Palm Beach Post

A collection of faith and community leaders demanded action Monday from Palm Beach County officials on a host of problems, including biased policing, a lack of affordable housing and a scarcity of mental health resources.

Leaders of PEACE, which stands for People Engaged in Active Community Efforts, hosted the group’s annual action assembly at the Palm Beach County Convention Center on Monday evening. There, they questioned Palm Beach County Sheriff Ric Bradshaw and Housing & Economic Development Director Jonathan Brown, as well as Ann Berner of the Southeast Florida Behavioral Health Network, on what progress has been made toward several goals.

Their answers didn’t always square with what PEACE’s leaders wanted to hear.

Rev. Cori Olson began the night by reading aloud a list of the night’s topics and PEACE’s proposed solutions. Before the officials took the stage to respond publicly, Olson described the roundabout denials they’d already given in private: attempts to delay, deflect and deceive, she said, disguised as polite policy talk.

Monday was the officials’ opportunity to either voice their support for PEACE’s proposals or explain to an estimated 1,000 attendees why they wouldn’t. Many who attended came with children, grandparents, neighbors and co-workers. Some listened through headphones with the help of a Spanish translator while the officials addressed their respective issues.

Like Bradshaw, and the data collection PEACE hopes will help combat biased policing; Brown, and the proposed funding meant to uplift low-income renters; and Berner, and the specialized team of clinicians PEACE says is lacking from the county’s mental health resources.

“Officials will give a clear ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ ” Olson instructed before the questioning began. “Those are the only things we’re interested in. Yes or no.”

Their responses were never so succinct. Attendees often had to wait for cues from PEACE moderators to know whether a sidelong answer deserved their praise or scorn.

By the end of the night, the exchange had fallen into a familiar routine: Answer, pause, “That sounds like a yes!”, then raucous clapping. Answer, pause, “Is that a no?” and silence — never jeers, or boos. Attendees agreed early on that silence was a louder form of disapproval.

Palm Beach County Sheriff Ric Bradshaw attends for the first time

When asked if the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office tracks data on all traffic stops — including those that result in a written warning and those that don’t — Bradshaw offered a long version of “not yet.” He pointed to the department’s recent adoption of body-worn cameras and dash cameras as a form of data collection but said “it can’t be tabulated.” The crowd stayed quiet.

The sheriff added that PBSO is in the process of upgrading its in-car computer system to collect data on traffic stops that result in only verbal warnings, including a driver’s race, ethnicity and the reason they were stopped. His tentative promise of an August 2025 rollout date is later than PEACE envisioned, but its moderators applauded the step nonetheless.

Teri Barbera, PBSO’s spokesperson, said the change will cost the agency nothing.

Bradshaw’s presence alone was a victory for PEACE and a welcomed surprise for returning attendees. According to Paige Shortsleeves, a lead organizer with the group, Bradshaw, a candidate for reelection this fall, either ignored or declined PEACE’s invitation to its annual event for the better part of the past decade.

His appearance Monday was his first.

Housing director blames developers for lack of affordable rent

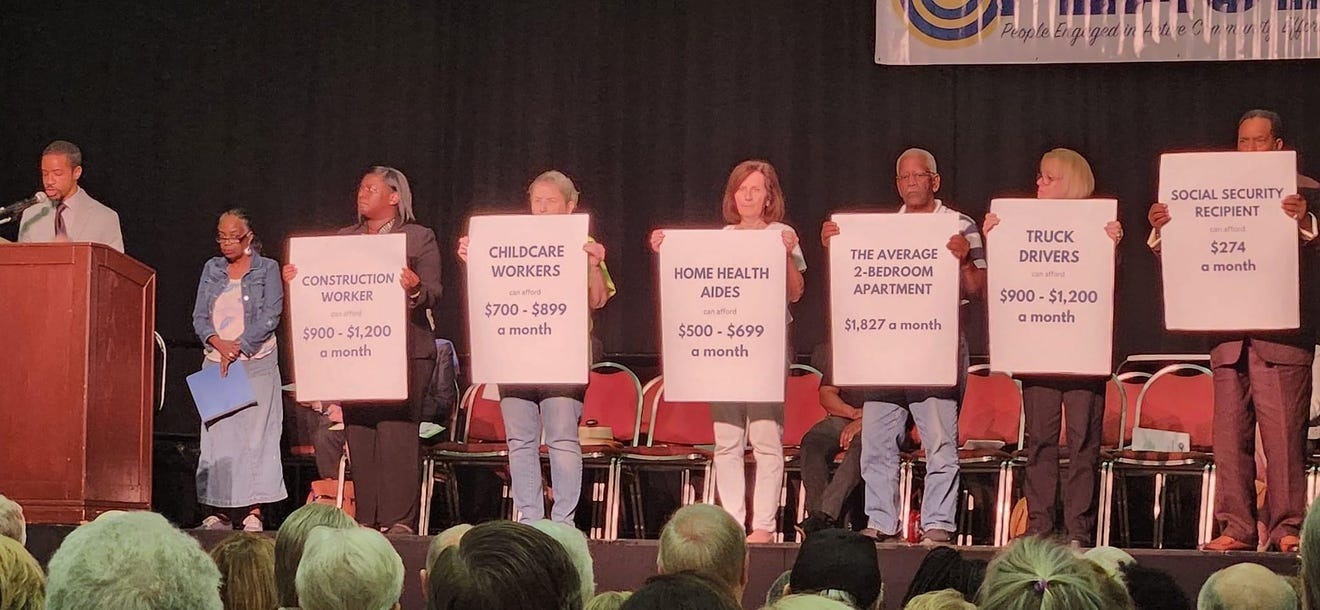

Moderators addressed county Housing & Economic Development Director Jonathan Brown next. They described a scarcity of affordable housing in Palm Beach County and noted that the county’s efforts to address the problem have been focused on “workforce housing” for people in jobs like teaching, fire rescue and law enforcement.

They argued that there needs to be more efforts to help those with lower incomes who have even fewer housing options.

When asked if he would support the creation of a county ordinance that prioritizes affordable housing for families making less than 60% of the area median income, Brown gave an immediate yes.

He said he would “absolutely” carry out the wishes of the county commissioners, should they choose to move forward with such an ordinance. He also agreed with PEACE’s suggestion that families earning less than $59,000 annually should be able to rent without spending more than 30% of their income on housing and utilities, but said that the reality is often different.

Brown encouraged attendees to talk to developers, who he suggested had more power than him to create positive change for low-income renters.

He pointed to the $200 million housing bond that county voters approved in 2022 to provide affordable and workforce housing. The number of developers who submitted proposals for the bond to build for people making 60% or less of the area’s median income was “very low,” Brown said.

“We need to encourage our developing community to be part of the solution so that we can address housing for our most vulnerable population,” he said, offering the first and only call to action of the night.

Health network CEO declines request to form additional mental-health team

The night’s final speaker was Ann Berner, CEO of the nonprofit Southeast Florida Behavioral Health Network which disburses money from the state for behavioral health services. When asked to commit to funding and managing an additional treatment team of specialized clinicians to combat Palm Beach County’s worsening mental health crisis, Berner wouldn’t give a firm “yes.”

“I don’t quite have the power that you suggest,” said Berner, whose agency contracts with the Florida Department of Children and Families to provide behavioral-health services to Palm Beach, Martin, St. Lucie, Indian River and Okeechobee counties. The five counties have a combined population of about 2.25 million people.

Her denial made for one of the more tense exchanges of the night. Berner told the PEACE moderators that funding an additional team would mean pulling money from other programs, something she couldn’t commit to without exploring other options further.

Berner said Palm Beach County has four teams already — two for the general public, and two for those in the criminal justice system — that adhere to the specialized program PEACE has endorsed, called Florida Assertive Community Treatment. FACT teams are made up of psychiatrists, nurses, mental health counselors, substance-abuse specialists and employment specialists who provide ongoing care for adults diagnosed with a mental illness.

The teams available to the general public serve 126 clients total, but PEACE leaders say there are thousands more in Palm Beach County who need the help. Berner said there isn’t room in the current budget to fund such an addition.

She tried to cut the questioning short, without success. At one point, she asked state Rep. Jervonte Edmonds to take her place at the mic to address funding for the proposed FACT team. Moderator Ruth Hook told him to sit back down.

“You’re the one with the money,” Hook told Berner. “This is your job.”

Despite PEACE’s prodding and insistence that she could find the money, Berner wouldn’t commit to adding another team of clinicians or even recommending it at an upcoming board meeting. She instead urged moderators to work with her on solutions she deemed more achievable, though she did not expound on what those were.

“We’re saddened,” Rev. Latifah Griffin, who moderated Berner’s session, said afterward. “From January to March of this year alone, Palm Beach County had 49 deaths by suicide. No county had more.”

By then, Berner had already left the stage.

View the original story here.