By Shira Moolten, South Florida Sun Sentinel

Martin Van Buren’s life began to unravel the day he ran a red light in the suburbs of Orlando, though he didn’t know it yet. A police officer pulled him over and left him with a hefty $262 ticket, a sum the 18-year-old could not afford on his $12-per-hour call center salary.

Soon Van Buren was subjected to a series of tasks: driving school, for which he also had to pay out of pocket, finding time in his work day to appear in court, and starting a payment plan, because he couldn’t pay the ticket in full and make rent at the same time. Though his situation began as a routine traffic ticket, the penalties he faced were steep. When he missed a few of his payments, the court had his driver’s license suspended.

Van Buren was left scrambling: He had to get to work in order to pay the original ticket, the added fines, and a license reinstatement fee on top of all his living expenses, but he could no longer drive there. He started siphoning money away for Ubers, sometimes the bus, once even a taxi. But he was still falling behind; he estimated that he probably spent about $500 on transportation in four months, more than he would ever have spent on gas.

“It took about four months before I realized this is not sustainable,” Van Buren, now 27, told the South Florida Sun Sentinel. “Something’s gotta give if I’m gonna get back to where I need to be.”

So he got back in his car and started driving, a criminal misdemeanor under Florida law.

The issue of driving with a suspended license received national attention over the last few weeks after a viral video showed a Michigan man attending a Zoom court hearing about his driving with a suspended license charge — from his car. In the days following, Corey Harris’ predicament became a comedic sensation. First it was reported that his license was suspended over unpaid child support, then a clerical error that wasn’t his fault. Later it came out that he never had a license in the first place.

Even with its contradictions, Harris’ case brought attention to a grim reality that Floridians deal with regularly: In a state that relies on driving, license suspensions keep people out of work, unable to get to doctor’s appointments or drop their kids off at school. Some say the system is necessary to keep dangerous drivers off of the streets. But license suspensions rarely have to do with a person’s driving ability. Instead, courts overwhelmingly issue them as punishments for failure to pay fines, meaning a traffic ticket can quickly turn into a criminal record, jail time, and thousands of dollars down the drain.

“There’s a percentage of those who just get caught up in this snowball effect,” said Broward Chief Judge Jack Tuter, “and by the time they get around to seeing how serious it is, they’re lost.”

Critics of the current system say it targets low-income people with debts piling up and a confusing bureaucracy they must navigate in order to pay them off, so they choose to break the law instead. Several conservative and progressive states have removed the use of suspensions as punishments for failure to pay altogether, but Florida has not, despite proposed legislation each of the last several years that seeks to do the same thing. That’s because unlike other states, Florida’s court system subsists off of fines and fees, which make up a large chunk of county clerk’s office budgets.

“They’re regressive taxes,” said Sarah Couture, the Florida State Director for the Fines and Fees Justice Center. “And they’re destroying people’s lives. Yes, I’m sure there’s a small number of people who willfully do not want to pay, but judges have tools to deal with those people. A majority of people want to pay, they’re just not able to. They lose hope, and they give up.”

Clerks say license suspensions are a necessary tool to obtain the money their offices rely on to function, and they can operate only within the confines of the state laws that made it that way. As an alternative to removing the system altogether, local officials have made steps to reform it, such as through simpler payment plans, reduced fees when tickets get sent to collections, courts that deal in driver’s licenses specifically, and civil citations rather than criminal charges for driving with a suspended license.

A few months after Van Buren began to drive again, a police officer scanned his license plate number, saw his license was suspended, and pulled him over, according to a probable cause affidavit. He had not committed any crimes besides choosing to drive that day. He didn’t get arrested, but he ended up with a court date and a $2,000 fine on top of the speeding ticket he was still trying to pay off.

“I tried to explain my situation, and of course no one cares,” Van Buren said. “It’s not their job to make exceptions or really empathize with individual situations. So he was just like ‘yeah, I get it man, but here’s your ticket, figure it out.’”

The numbers

Beginning in 2018, Miami-Dade County Commissioner Eileen Higgins began working with a design firm called Ker-twang to interview people whose licenses had been suspended. Two years later, the county approved a Driver License Suspension Task Force and began testing a court that would help people specifically with driver’s license issues.

The stories they heard were often depressing: The first person Ker-twang co-founder Harris Levine ever interviewed was a college student who had a $90 speeding ticket she hadn’t paid. She got pulled over, her car was impounded, and she had to use her rent money to get it back. Because she couldn’t pay rent, she had to sit out a semester in college. She told administrators that her grandmother had died.

Another woman, four months’ pregnant, spent the night in jail over unpaid fees. A third woman Levine encountered had paid off the red light ticket that suspended her license, but not the $60 license reinstatement fee, so she was hit with a driving with a suspended license charge while on her way to chemotherapy.

Over 716,000 drivers in Florida had suspended licenses, according to a 2023 report from the Fines and Fees Justice Center, which used data from the Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles.

Couture, who authored the report, used data on suspension notices issued from 2019 to 2022 to estimate that roughly 80% of all notices issued in South Florida were because of court debt, not dangerous driving.

As of earlier this month, close to 70,000 suspensions in South Florida were solely over failure to pay fines and fees, according to the Florida motor vehicles department.

The system harms all Floridians economically, critics argue, not just those with the suspended licenses. Suspensions take away people’s ability to work and how much they can spend, while driving up insurance rates. Those whose jobs rely on driving could end up fired. A New Jersey Department of Transportation study found that over 40% of drivers lost jobs because of suspensions and struggled to find work.

Florida’s insurance premiums are about $78 higher each year due to suspended licenses, the Justice Center report says; the state is one of the most expensive for car insurance. Law enforcement officials say people who commit hit-and-runs often name a suspended license as a reason for fleeing the scene of the crime.

‘Waiting to get pulled over’

Duane Thwaites spends much of his time walking people through a system they don’t understand. Sometimes they are homeless, or can’t read. Sometimes the bills pile up so high that they will never pay them back in full.

Thwaites works for Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, an organization that helps people with past convictions return to society, though he does much of his advocacy on his own. Recently, he has been trying to help a man who ended up with $1,400 in court costs after two prior felony cases where adjudication was withheld. One day, late on a few of his payments, the system kicked him out, Thwaites said. But the next day it was working again, so the man assumed the payment went through. It turned out his license was suspended.

“He was like, ‘well, why?’” Thwaites said. “He then refused to participate in the system. He’s like ‘yeah, they’re stealing my money, they’re still suspending my license.’ The following month came, he’s like, ‘well, they don’t want my money.’”

Two years later, Thwaites bumped into him. He still didn’t have a license; Thwaites told him he could help him get his license back.

He said, “‘Well, if I have to do all this extra stuff, I don’t want it,’” Thwaites recalled. But he was able to convince the man to get back on a payment plan.

Payment plans allow people who can’t fully pay off their fines to get their licenses reinstated as long as they pay the $60 reinstatement fee and make their payments on time. Some South Florida clerks have worked to improve the system so that people can pay as little as they need, with monthly payments as low as $5 or $10 in Palm Beach County and Miami-Dade.

Still, people say the system is often unforgiving and difficult to navigate, perhaps as big of a burden as the costs themselves. Even people who work within it don’t understand it at times, Thwaites said.

“No one knows really how to get it done,” he said. “No one within the system fully understands what’s supposed to be done. So I’ve had people who, they went and they saw person A that works at the DMV and the DMV tells them one thing. Then they go to person B and that person tells them something completely different. And person C it’s completely different from both A and B.”

The bureaucracy is made more convoluted by the fact that each South Florida clerk’s office has its own system. Many people have tickets suspending their license in more than one county, but officials have not yet figured out a way to consolidate cases, leaving them juggling multiple payment plans.

“At the moment unfortunately we don’t have the technological capability to be able to put everyone on the same payment plan across jurisdiction,” said Miami-Dade County Clerk Juan Fernandez-Barquin.

Other aspects of the system have become outdated. Many people do not know their licenses are suspended at all because notices are sent out by mail, to old addresses.

“A lot of people find out their license is suspended by getting pulled over and they’re told by a police officer,” said Levine, of Ker-twang, “which then can escalate into really serious stuff.”

One person he spoke to found out his license was suspended only when he got fired from his job.

Oftentimes going to the courthouse in person is the easiest way to make payments, but the people who need to can’t legally drive there.

“It’s a thing which starts off small but then can lead to really big problems,” Levine said. Many of the people he spoke to have had license suspensions for up to 15 years.

“One guy I talked to was like, ‘I want to get this fixed, I don’t know how to get it fixed. I’m just waiting to get pulled over and then when I get pulled over and taken in, I’ll start the process of dealing with it then.’”

A ‘predicament’ for Florida’s clerk’s offices

Local clerk’s offices are the only constitutional officers in Florida that rely heavily on the fines and fees placed on people who go through the system, according to Barquin: county tax collectors, property appraisers, sheriff’s offices and supervisors of elections all get their funding elsewhere.

“We’re in a unique predicament,” he said.

The money is an unstable revenue source for clerks. But the funding system is baked into the Florida constitution, so local offices can’t alter it without the passage of new legislation.

“More stable funding sources will provide significant help for our office and the communities we serve,” the Palm Beach County Clerk’s Office 2024 budget report reads. “The funding sources for our court operations as determined by the Florida Legislature continue to be unstable with significant changes possible each year, making long-term financial planning difficult for our office and other Clerk’s offices around the state.”

In 2023, the Palm Beach County Clerk’s Office made over $6 million from traffic ticket cases, a little less than 30% of the total revenue of over $28 million.

Each year, the Fines and Fees Justice Center has fought for state legislation that would remove license suspensions over fines and fees, Couture said. Each year, those bills have failed, primarily, she said, because of the clerks of court.

“The bill has been killed every year that we’ve run it,” Couture said. “The only opposition is the clerks of court. They believe, they’ve testified in committee hearings in Tallahassee, on this being the only tool they have to compel payment.”

Local clerks say that the Justice Center is too strong in its position without offering an alternative for how their offices would get paid. The Justice Center believes that removing the system altogether would not actually reduce clerk’s budgets because it would allow people to work and therefore pay off their fees more easily. Some studies in other states have shown that suspensions have little to no effect on court revenues.

“What I would say to advocates who do not want this to be part of the way clerks office or courts operate, I would submit they should propose along with their proposal, what is the alternative?” said Palm Beach County Clerk Joseph Abruzzo. “To say we’re not going to fund the clerks of court and courts in general, that would be not likely … it’s not realistic. It’s not realistic just to say, ‘We want you to end this and that’s it.’”

Barquin shared similar sentiments. Over 50% of the budget for his office comes from fines and fees, he said.

“The FFJC tries to control narrative on this,” he said. “and the public is not educated on what the issue is. The vast majority of the public would also agree if someone does something wrong there has to be a consequence. But the FFJC does not want to work with us to try to get away from current model … we tried to negotiate with them in good faith last legislative session but they wouldn’t budge from their position.”

‘The most horrendous, traumatic thing’

Addy Lubin, 47, says a clerical error resulted in the worst night of her life.

The Miami Springs resident was a marketing manager for a cruise line when her license was suspended about a decade ago for failing to pay tolls. The cost of the tolls plus administrative and collections fees, which often add another 40% to the original ticket, turned into a couple thousand dollars, but at least Lubin could afford to pay.

Yet a few months later, she was driving in unincorporated Miami-Dade County when a police officer pulled her over and told her her license was suspended.

Lubin thought the state had reinstated her license. She had no idea it was suspended, but the officer arrested her anyway, she said. Having no knowledge of the crime should be a civil infraction, but that’s “subjective,” Lubin said.

She spent the night in a dirty county jail cell with approximately 30 other women, several of them apparently prostitutes arrested during a sting operation. There was only one toilet; the smell was rancid. Lubin didn’t sleep.

“It was the most horrendous, traumatic thing that I’ve ever experienced,” she said.

Now, Lubin works in marketing for a toy company and serves on the board of BOLD Justice, an advocacy group made up of local clergymen based in Broward. The group fights to end “unnecessary arrests” across the county, including over traffic misdemeanors like driving with a suspended license, according to Pastor Noel Rose, one of the committee chairs.

Activists have raised concerns about the subjectivity of arrests.

“As human beings, we have our good days and our bad days,” Rose said. “There are times my bad days mess with my professionalism. So it shouldn’t be left up to me.”

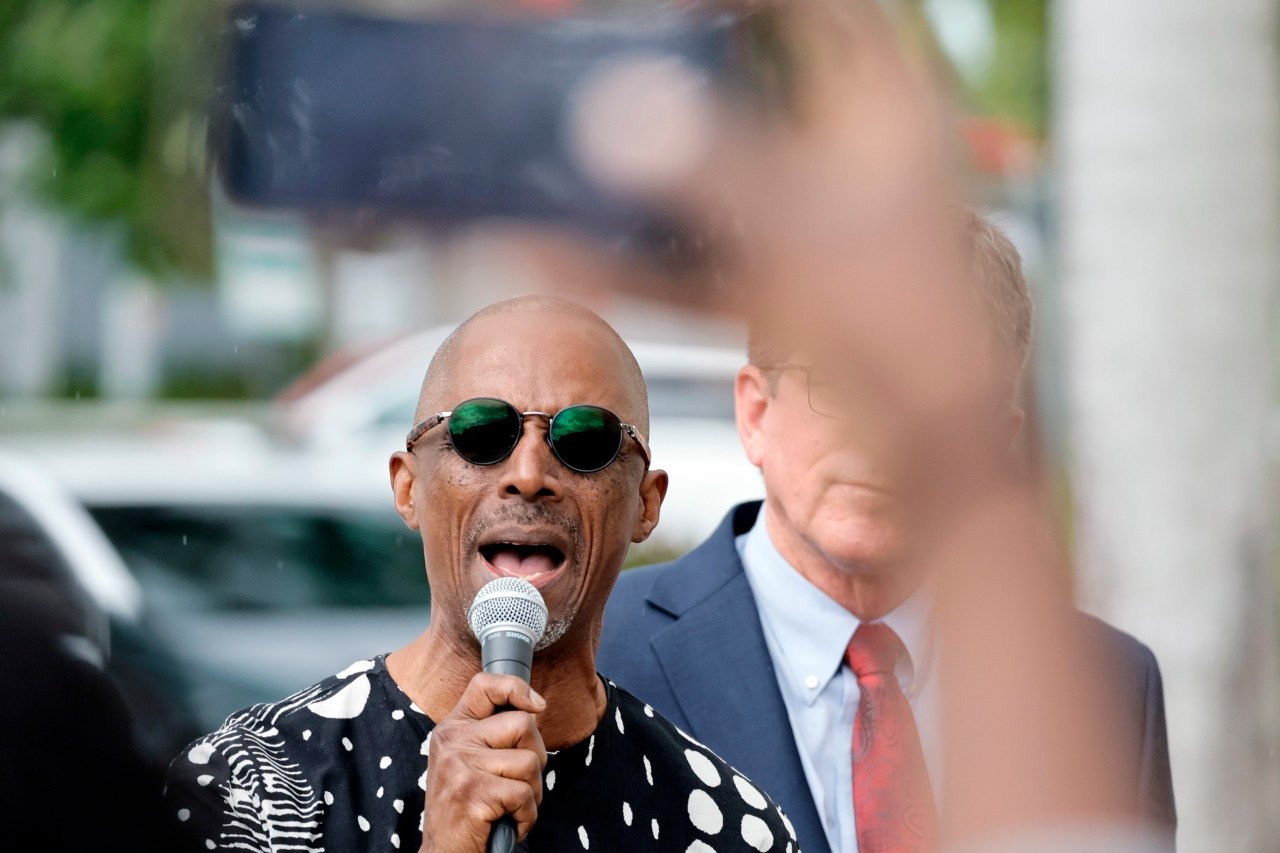

Recently, BOLD Justice staged a protest against the Broward Sheriff’s Office, saying that deputies were continuing to arrest drivers for misdemeanor traffic offenses like driving with a suspended license, despite promises that they would no longer do so. Broward County has adopted an adult civil citation program for misdemeanor offenses, which drivers should be diverted to instead, protesters said.

In response to questions about whether deputies are still arresting people for misdemeanor traffic offenses, the Sheriff’s Office referred to its policy on the civil citation program.

“Our deputies will continue to follow the law and criteria for Broward County’s Adult Civil Citation program,” spokesperson Veda Coleman-Wright said in a statement.

The policy states that misdemeanor traffic offenses are ineligible for the program, even though Broward County’s ordinance creating the program only mentions felony traffic offenses, not misdemeanors.

Technically, the decision of whether to divert adults into a civil citation program or arrest them is up to an individual officer’s discretion under state law. Still, local law enforcement agencies could encourage officers to cite people rather than arrest them.

Miami-Dade County is also working on a civil citation program with the support of the local chiefs of police that encourages officers to issue citations rather than criminal charges for driving with a suspended license. Ultimately, arrests would remain up to the officers’ discretion, however.

Law enforcement officials say that suspended license charges typically accompany other offenses and are rarely reason enough alone to arrest someone. BOLD Justice argues that their information says otherwise.

“If folks have other issues, that should be dealt with,” Rose said. “But there are cases of folks who, their only transgression, they had a busted tail light or they ran the toll and they did not pay the toll, and so their license gets suspended, and they have no idea until they get pulled over.”

Local offices work on reforms

Since the creation of Miami-Dade’s Driver License Suspension Task Force, the county commission, clerk’s office, courts and state attorney’s office, and law enforcement have been working to reduce the backlog of license suspensions in the county.

They will soon officially launch the Driver License Assistance Court, where people can figure out everything they need in one place, said Higgins, who helped create the task force.

They are also updating their technology. Before, the clerk’s office payment plan wouldn’t automatically deduct from people’s bank accounts, while people were missing their court dates because they had no reminders, Higgins said.

“The technology they were using was just, who the heck knows what era it was from,” she said. “But it certainly wasn’t modern era.”

The clerk’s office has begun offering extended hours at some locations, important for those who can’t afford to miss work. It has reduced the collections fee from 40% to 30%, and now allows people to have their cases removed from collections with no fee if they come in person, Barquin said. His office has helped reinstate over 38,000 licenses so far and waived $3.6 million in collections fees.

The Palm Beach County Clerk’s Office was the first to hold Operation Green Light, a state-mandated special day where people can pay the fines suspending their licenses with reduced fees, now held in every county. The office has also worked to help improve the payment plan system through text reminders and calls and participated in community events and “mobile office hours” at libraries and city buildings.

Broward County Clerk Brenda Forman did not respond to a request for an interview for this article.

Some reforms have also taken place within Broward’s court system. The State Attorney’s Office currently drops suspended license charges against people if they get a valid driver license within 30 days of the arraignment date, according to spokesperson Paula McMahon. If they are unable to do so within 30 days, they get another 30 days to join a diversion program called License to Drive, which gives them a year to get a valid license and have the charges dropped.

Still, local offices can do only so much without a change in state law.

“We don’t have a say in the policy, we just have to administer what the state lawmakers and what the state has decided,” said Abruzzo, the Palm Beach County clerk. “That obviously is a major source of our revenue. The things that are in my control, we try to do everything we can to keep our drivers on the road and to get them back on the road.”

Just the other day, a police officer stopped Van Buren in a Wawa parking lot because of his window tints. He gets pulled over so often, it’s almost routine, though the interaction still put him in a bad mood before work. His girlfriend says his lowered black coupe is a “cop magnet.”

Years after his first suspended license charge, Van Buren was saddled with another one. It was the beginning of the pandemic and he was jobless at the time, but he paid off the fees. Then he got pulled over. Again, the officer had run his plates and saw that his license was suspended. When Van Buren tried to show the officer the court receipts online, he wrote the ticket anyway.

Later, after emailing the court several times, he was able to get the ticket removed. But his faith in the justice system had already grown more tenuous.

“Before, growing up, I never really had any particular thoughts about it,” Van Buren said. “After my experience, I know it’s a money machine.”

View the original story here.