March 15, 2017. Folio Weekly.

JACKSONVILLE, FL — Behind a bright façade of economic development, population growth and urban renewal, Jacksonville has a secret: It doesn’t quite know what to do with—or about—the homeless. As smiling politicians and businessfolk cheerfully scoop ceremonial shovelfuls for the cameras and onlookers excited at the prospect of a new restaurant, job or shop, in the far background, people climb out from under blankets of newspaper, rise from beds of concrete and shoulder through the day, weighed down by their lives’ figurative and literal luggage.

Currently, city council is debating a $2 million settlement based on its alleged violation federal anti-discrimination laws, which requires changes to the zoning code that advocates say brings the city in line with the law and opponents believe takes away neighborhoods’ say in zoning variance requests. Simultaneously, two local clergymen allege that the mayor is threatening to withdraw his support for the sorely missed Jacksonville Day Resource Center for the homeless if they speak to the media.

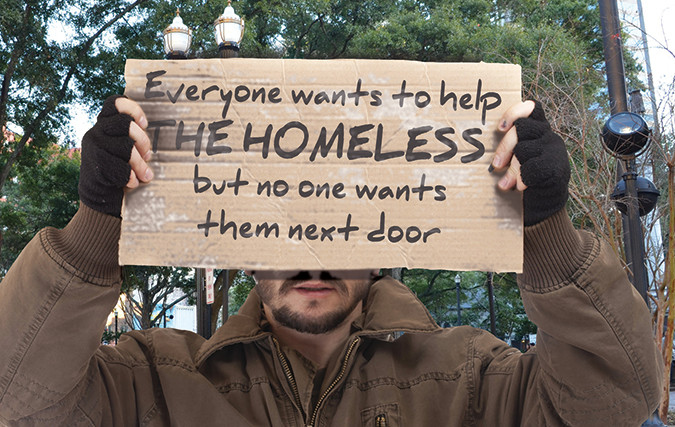

Both issues cut to the heart of the city’s longstanding quandary about how to best address homelessness. To some, the homeless are invisible, to others a subject of pity or scorn or indifference; many of the well-heeled and well-fed would rather they just go away. Though the community at large commends those who do care enough to lift a finger or extend a helping hand, most just avert their eyes.

But indifference does not provide housing nor fill bellies and, as the city tries to grapple with the issue, little changes, except the growing need. The 2016 point-in-time count tallied 1,959 homeless in Duval County. The Florida Department of Children & Families’ Office of Homelessness says point-in-time counts comprise only one-quarter of the number of people who experience homelessness in a given year. If so, then nearly 8,000 people were homeless in this community at some point in 2016. Based on data and Duval County Public Schools’ data, more than a quarter of the homeless were children.

As with all cities, homelessness is particularly pervasive in the urban core. In Downtown tonight, 400 people will sleep in a shelter, a tent or out in the elements. And until something changes, and soon, that number is likely to grow.

____________________

NO LOITERING

After years of discussion, in the summer of 2013, a wide-ranging community partnership enabled the Jacksonville Day Resource Center to open. Billed as a one-year pilot program, the center offered a safe place for people to eat, shower, do laundry, use the Internet and phone, and connect with resource providers and other services. It was a proud day for Downtown development and then-Mayor Alvin Brown, for whom opening the center fulfilled a campaign promise.

A year later, the program, which provided services to approximately 150 people every day, was extended. In September 2015, two months after Mayor Lenny Curry was sworn in, the center released a statement on its Facebook page that his budget was forcing it to close on Oct. 1 that year. (Dawn Gilman, head of Changing Homelessness, disputed that account, telling the Florida Times-Union at the time that the center knew it would close on Oct. 1 even before the mayoral election.)

Without a day center, since 2015, homeless people have increasingly frequented parks, businesses and public buildings in the Downtown core. Of late, the numbers of homeless congregating in Hemming Park has become something of a touchstone issue. There are few restroom facilities available, and the Main Library has become a way station of sorts, though it is not designed, nor equipped, for such use. It is not uncommon to see people resting, even dozing, in the library, surrounded by backpacks and other luggage.

Businesses in the Downtown core have also been inundated at times. Some businesses even have Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office personnel’s cell phone numbers on speed-dial when they need help escorting out those who loiter or disrupt business, such as the many mentally ill or those with serious substance abuse issues who live on the streets.

Meanwhile, Friends of Hemming Park, the nonprofit that has a contract with the city to manage the park, which the T-U reported in 2015 warned that it was “not equipped” to fill the void left behind by the center when it closed, had been at odds with the mayor’s office. At a November city council committee meeting, Curry’s chief administration officer indicated that the mayor wanted to take back control of the park, based on his perception that the nonprofit had not been successful at abating the numbers of homeless.

In a Folio Weekly Backpage Editorial on Feb. 15, Wendy Jenkins urged the mayor and city council to see the humanity in homeless people like her, writing, “Out of sight, out of mind is not a solution to homelessness; the solution is actually trying to do something real to help those of us who are living in the streets … . Look out the front windows of City Hall and see the human beings who are just trying to survive and hoping for something better.”

On March 9, Friends reached a tentative $415,000 six-month contract extension with the mayor’s office. (The contract still requires City Council approval.)

Friends’ interim CEO Bill Prescott told FW that the new contract shifts some of its focus from providing programming to maintaining peace and aesthetics, efforts he says are improved by last month’s ordinance that allows JSO to ban people who violate park rules for a year. Prescott also said private security will be on hand from sunup to sundown and that they will monitor how many calls related to the park are made to JSO. Of Friends’ private security, which has been monitoring the space since August, he said, “That has made a tremendous difference.”

There’s only so much that Friends can do, and advocates have continued pressing the mayor to include funds for reopening the day center in his proposed budget. A study by Clara White Mission determined that it would cost $311,200 to reopen the center five days a week; somewhat less to open it three days each week. At a publicly noticed meeting on March 9, councilpersons, including John Crescimbeni and Aaron Bowman, two contenders for leadership positions with that body, stated their unequivocal support for reopening the center, while another councilman lamented how he dislikes seeing people sleeping in the streets.

Some argue that there are places that provide services to the homeless during the day, such as the Mental Health Resource Center, or Quest. While the small, nondescript white building on the far end of Church Street does provide respite from the elements as well as bathrooms, drinking water, television and mental health professionals for its clients, it does not offer many of the services the day center provided, such as connections to other resource providers, Wi-Fi, computers for public use, laundry facilities, etc.

____________________

THE MAYOR VERSUS ICARE

One group that has been particularly vocal about reopening the day resource center is the Interfaith Coalition for Action, Reconciliation and Empowerment (ICARE), a multi-faith coalition that focuses on justice and human-welfare issues.

ICARE has been lobbying the mayor to reopen the center for more than a year. Last year, at its annual Nehemiah Assembly, a well-attended event at which public officials are called onstage and asked a series of questions related to whichever of ICARE’s areas of focus they have power to change, Mayor Curry was put to the test on the resource center.

ICARE co-president Pastor Phillip Baber told FW that they’d believed the mayor was going to agree to fund the center in his next budget. So it came as a surprise when they asked him at the assembly and he said “no.”

Instead, Pastor James Wiggins, last year’s co-president of ICARE, said, “He used it as a platform to do an ad for the pension tax.”

In a video of that assembly, which was shown at ICARE’s pre-assembly rally on Feb. 28 at Abyssinia Missionary Baptist Church, the mayor makes an impassioned argument for the pension tax, at one point even resorting to shouting at the crowd sans microphone.

“Until the pension is solved, we don’t have the money,” Curry says in the video.

In a series of follow-up questions, the mayor seems to agree to consider funding the center if the pension tax passes.

“I will examine the numbers. I believe in the resource center,” Curry says.

When the pension tax referendum passed last August, members of ICARE thought they’d finally be able to convince Curry to fund the center. So far, their efforts have not been successful. At a Feb. 6 meeting at City Hall, which was also attended by Sheriff Mike Williams, Wiggins and Baber said that the negotiations took a turn for the worse.

They told FW that, initially, Curry refused to meet with all 15 members of ICARE who were present. “He wanted it to be a backdoor meeting for just the [co-]presidents,” Baber said. Caught off-guard, Baber and Wiggins said they tried to convince the mayor otherwise, but he insisted, so they agreed to talk in private. (Wiggins was co-president last year; this year, Baber and Geneva Pittman Williams are co-presidents.)

“The mayor came in and began to say some things that I felt weren’t really healthy,” said Wiggins.

Baber said the mayor was “very adversarial, even hostile,” and spent 30 minutes trying to figure out who had scheduled the meeting; he and Wiggins said that the mayor also warned that if they went to the press, he would not support reopening the center. Baber opined that the mayor was trying to “muzzle us.” (The mayor did not answer FW’s questions about this version of events, but on March 10, the T-U reported that he unequivocally denied it. Sheriff Williams did not respond to FW’s inquiries.)

Eventually, the mayor agreed to meet with all 15 present, but Wiggins and Baber said little, if anything, was accomplished.

Regarding their decision to speak to the media, both Baber and Wiggins said that they just want the mayor to take the lead on homelessness instead of giving lip-service, then dodging an issue that affects the most vulnerable citizens, which they believe the city has a moral obligation to serve; Baber noted that ICARE is going to continue having “a good working relationship with the press.

In his speech at the Feb. 28 assembly, Wiggins recounted the foregoing to a few hundred attendees. Speaking before him, Pastor Baber, who has a fiery, evangelical speaking style, said, “Mayor Curry can choose to ignore the needs of—the very existence of—the homeless men, women and children in our city. Or he can choose to make a change.”

Before the assembly began, Baber told FW that the mayor had yet to agree to attend this year’s Nehemiah Assembly; during his speech, Baber asked attendees to email the mayor urging him to attend. The mayor’s publicly available email account on the city’s website shows a flurry of correspondence on the matter that night and the next day. The following afternoon, the mayor’s executive assistant apologetically informed ICARE via an email provided to FW that due to a “prior commitment,” Curry would not be able to attend.

It is not clear where this leaves the day resource center or the homeless.

____________________

A HOME FOR LARRY

Fifty-seven-year-old Lawrence “Larry” Collins begins most days at 5 a.m., a habit he picked up in the Navy more than 20 years ago. After the death of his sister two years ago, the 6-foot-3-inch New Jersey native, with a warm smile and deep vocal timbre, started looking for a place with good subsidized housing. Upon finding Ability Housing on the Internet, Collins relocated from Atlanta to Jacksonville, where his mother was born.

Over his adult life, Collins has had some unfortunate turns of fate; when he was a young man in college, his mother’s untimely death led him to drop out and hitchhike across the country to California, where he wound up adrift with no anchor.

“I was homeless on the streets of Los Angeles,” he said.

Rather than settle for taking handouts, Collins started working at the mission where he slept and eventually landed a paying job elsewhere, bought a car and started dating. Though things were looking up, Collins longed for something more. “I felt like my life was going nowhere,” he said.

Then in his mid-20s, he signed up to serve his country. After waiting a year for boot camp to begin, Collins’ plans to join the Air Force were stymied by an injury just before he was to leave. Waiting another year for the next camp meant he would be too old to enlist in the Air Force; when a friend told him the Navy would still accept him, that was all he needed to hear. He signed on the dotted line and shipped out a week later.

From 1987-’91, Collins traveled the world with the Navy. Speaking of being stationed in the Red Sea during Desert Storm and Desert Shield, he paints a vivid image of a young man keeping fighter jets in the air, ordering parts 12 hours a day, seven days a week; in his off-time, shooting videos for fellow service members to send home and taking in picturesque Middle Eastern sunsets on deck of his aircraft carrier.

He also had a string of bad luck. The distance drove an irreparable wedge between him and his new wife and he was involved in four car accidents, none of which were his fault. The injuries from the accidents caused permanent damage.

“I’m lucky to just be walking, you know,” he said with unexpected cheer.

Today Collins fights though peripheral neuropathy, which has similar symptoms to diabetic nerve pain (he’s not diabetic), and gout that makes his feet swell painfully at times, despite careful watch over his diet. Through it all, he gets up at five to work as a day laborer, often working 40 hours a week. Between his diverse areas of expertise, including concrete, mechanics, and much more, and his go-get-’em attitude, Collins has no problem getting work most days, which he considers a blessing, explaining that he has bills.

Collins is currently appealing to the Navy to increase his disability rating; that way he can save more and, when his conditions make staying on his feet difficult and painful, work less.

“I don’t think I could work a full-time job right now because of my health,” he said.

Collins lives in Ability Housing’s Village on Wiley housing complex, a 43-unit community which houses people who have been homeless or are at risk of becoming homeless. Before that, Collins was staying in a rooming house off Mars Avenue that didn’t have heat. He has no shortage of praise for Ability Housing, proudly pointing out that nearly all his furniture was donated and speaking fondly of his case manager, who drops in at least a few times a week.

“They’re there with open arms,” he said of the nonprofit that provides affordable housing and connections to support services for the homeless and people with limited incomes, including disabled veterans like Collins. He considers himself blessed; aware that other disabled veterans scramble day-to-day to keep a roof over their heads and food in their bellies on extremely limited incomes.

_____________________

“THEY GOTTA LIVE SOMEWHERE”—JUST NOT HERE

Over the last two years, Ability Housing has had a 95 percent housing stability rate, well over the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development’s goal of 80 percent. It’s been so successful that the Central Florida Commission asked the organization to expand, leading it to launch housing developments in the Orlando area in recent years.

Some haven’t been quite so appreciative of Ability’s efforts in their own neighborhood, however. In 2014, Ability’s plans to acquire and rehabilitate a 12-unit apartment building to house disabled veterans in the Springfield neighborhood erupted into controversy. Some community members staunchly opposed the plan, and on May 29, 2014, the Planning Director provided a written interpretation that the proposed use was “categorized as a special use rather than a multiple-family dwelling, and as such, would be considered a new special use prohibited in the Springfield Zoning Overlay,” according to a July 28, 2015 letter from that department. That letter went on to state that the city’s Planning Commission had upheld the interpretation on appeal.

The May 2014 document states that Ability’s plans to house disabled veterans in a 12-unit apartment complex on Cottage Avenue was not a permitted multifamily dwelling; rather, based on Ability’s grant application to the Florida Housing Finance Corporation, the department found its requested use was “to serve chronically homeless adults without children,” which, taken with the assumption that “all residents will have a disability diagnosed by a licensed professional health care provider and it is anticipated that most residents will have a primary diagnosis of mental illness and a long history of psychiatric hospitalization,” and “importantly, [that] support services will be provided by community organizations.” This led the department to conclude that the proposal was a prohibited special use. Under the Springfield zoning overlay, special use is defined to “include residential treatment facilities, rooming houses, emergency shelter homes, group care homes, and community residential homes of over

six residents.”

Though some would say that this definition of a prohibited special use clearly and illegally discriminates against disabled people, the city would not budge. When Ability’s appeal of the written interpretation was denied, the Department of Justice opened an investigation in December 2015, the factual findings of which it provided the city last September, and subsequently joined a federal suit in December with Ability and Disability Rights Florida.

At issue was whether the prohibited special uses violated the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination against people based on disability and requires housing providers to make reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities. Ability Housing and the Justice Department took the position that the Springfield zoning overlay banned uses specific to people with disabilities and, further, that the zoning interpretation specifically banned Ability’s use based on potential residents’ disabilities in violation of that act.

In January, the parties reached a tentative settlement, the terms of which include:

- rescinding the zoning interpretation;

- five years of Justice Department oversight to ensure the city does not violate the FHA or the ADA;

- a $1.5 million grant for permanent supportive housing within the city for persons with disabilities, which will be awarded through a competitive grand process (the grant Ability was to use to renovate the apartment complex has long since expired);

- $400,000 to Ability and $25,000 to Disability Rights Florida to pay a portion of legal fees;

- amending the city’s zoning code and the Springfield overlay to bring it into compliance with FHA and ADA, specifically removing the bans on certain uses that by definition serve disabled persons, such as group care homes, nursing homes, hospice facilities, etc.

- “If somebody else wins [the grant], that’s fine; it was never about Ability Housing, it was about housing,” Shannon Nazworth, director of Ability Housing, told FW on Feb. 13.

But some still aren’t satisfied. Springfield Preservation and Restoration council, a citizens group that advocates for the neighborhood, opposes the settlement, particularly its mandated changes to the zoning code “on the grounds that the recommended changes to the Springfield Zoning Overlay and Historic District Regulations were drafted without appropriate community input; are unnecessary; are unfairly applied; and are potentially harmful to future development of the historic district,” according to its website. SPAR also contends that the changes, which apply to all of the city’s zoning code, not merely the Springfield overlay, will effectively “single out Springfield to be the default and de facto area in Jacksonville for disabled housing.”

SPAR’s Executive Director Christina Parrish told FW that while they don’t oppose the purpose of the settlement or bringing the zoning overlay in line with existing laws, their position is that it takes too much power away from neighborhoods, allowing the Planning Department to make changes without notifying the community and without their having a right to appeal.

“You’re giving a lot of authority to someone in the Planning Department with no notice to anyone else in the community,” she said in a telephone interview on March 1, later adding, “The rights of the disabled, while they’re absolutely critical, they shouldn’t trump the rights of everyone else.” Councilman Reggie Gaffney, who represents the district, noted that at the Feb. 28 city council meeting, the Office of General Counsel agreed to work with them to revise the legislation to address some of their concerns and meet the terms of the settlement.

Gaffney told FW that some residents are concerned that Springfield will become saturated with group homes like it was decades ago.

“I’m a mental health provider. If you come to my facility on a daily basis, you are going to see about 125 individuals that are sick,” he said on March 9. “ … The question that I may ask myself is, ‘Do you want that across the street from your house?’ and most people [are] going to say ‘no.’

“At the same time, they gotta live somewhere,” Gaffney continued.

Gaffney said that if OGC and SPAR could agree to an ordinance that meets with the terms of the settlement, including by possibly increasing the required distance between group homes from 1,000 to 1,500 feet, he would be in favor of it.

Asked about the day resource center, he said he supported reopening it.

“My preference is, I wish it would be somewhere else, not centrally located Downtown,” he said.

“But wherever it’s going to be, as long as we put the proper resources, that’s going to help that population become more stable. When they become more stable and we start focusing on these kids, we’re going to have a better city.”

View original article.