BY Tony Marrero, Tampa Bay Times

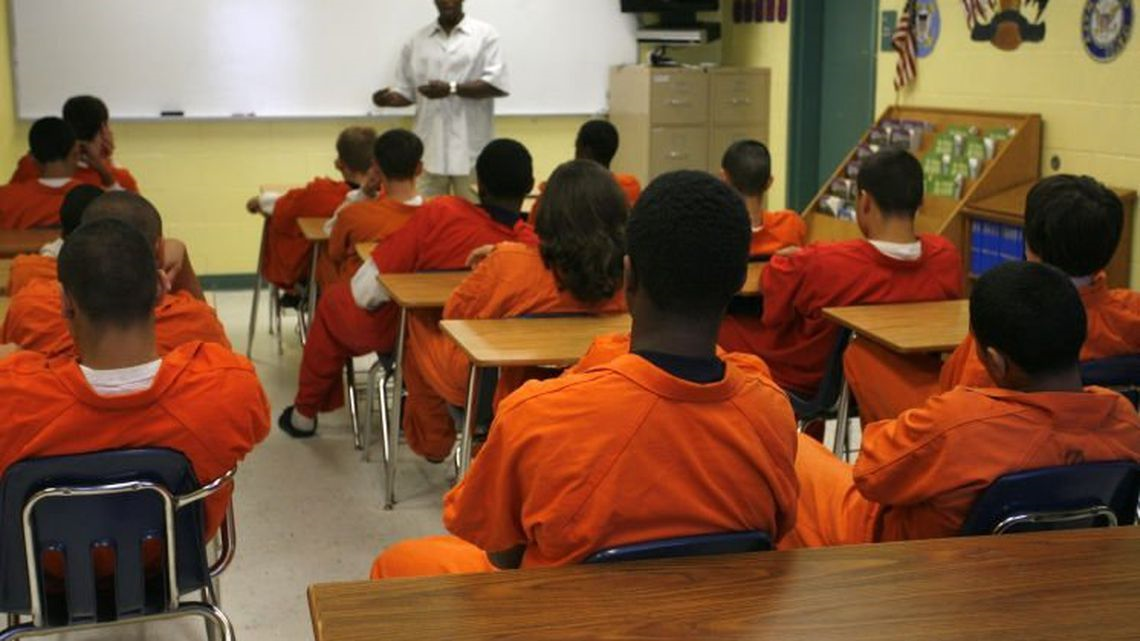

Too many kids are getting arrested, according to the Hillsborough Organization for Progress and Equality. Local officials agree, but differ on how to address the issue.

TAMPA — Arionna Thomas was just a fifth-grader when she brought a knife to school a few years ago.

Thomas, who said she was being bullied and going through other personal issues, faced arrest. Instead, she was placed in Hillsborough County’s Juvenile Arrest Avoidance program, where she got therapy and avoided an arrest record.

“I realized my self worth and that I wasn’t alone, and I think every kid should be able to have the opportunity that I was given,” Thomas said during a recent event hosted by the nonprofit Hillsborough Organization for Progress and Equality.

Too many children who could enjoy the benefits Thomas did are still getting arrested for first-time misdemeanors in Hillsborough County, potentially burdening them with records that could haunt them for years, according to the HOPE organization.

The group, more than two dozen local churches who advocate for social reforms, is pushing officials to create a secondary review process to divert more eligible children into the program. They say other Florida counties that use the process have a much higher rate of juvenile citations and a lower rate of arrests.

“For seven long years we’ve worked to reduce youth arrests by expanding the civil citation program, but every year, somewhere between 200 and 400 children are still unnecessarily arrested for first-time misdemeanor offense,” said the Rev. Bernice Powell Jackson, co-chair of HOPE’s criminal justice committee, during a virtual edition of the group’s annual Nehemiah Action event. “We can do better for our children because restorative justice is God’s justice.”

HOPE’s proposal for a review process is the latest call for action in a county that has been the target of criticism for the number of kids arrested here. Local officials have worked together to expand the program and lower the arrest rate, but nearly all agree there’s room to make the program more effective.

How to get there, though, is up for debate.

Evolving program brings some progress

HOPE first started pushing for juvenile justice reform in 2014. At the time, Hillsborough was a target of criticism for its high juvenile arrest rate and low numbers in the juvenile citation program.

In the program, children who receive the citations must agree to accept responsibility for the crime and enter a diversion program, which can include community service or restitution. They undergo assessments to allow authorities to create a program with services tailored to their risks and needs. If they fail to meet all the court mandates or are arrested again, the case is referred to the State Attorney’s Office for possible prosecution.

After Hillsborough State Attorney Andrew Warren took office in 2017, he announced an agreement between local law enforcement agencies and the courts that expanded the use of juvenile citations. Warren found willing partners in Sheriff Chad Chronister, who was appointed to his post later that year, Public Defender Julianne Holt and Chief Judge Ronald Ficarrotta.

At the time, 13 offenses were deemed ineligible for consideration for the program. In 2019, Warren, Chronister Ficarrotta and Holt announced an updated agreement that would pare that down to five ineligible offenses, where it remains today.

Those offenses are domestic battery (not including family violence), assault on a school employee or law enforcement officer, violation of an injunction, driving under the influence and street racing.

Then, in September, Chronister, Warren and Holt announced that parental consent would no longer be required to participate. Officials said some eligible kids were denied because of problems getting consent from their parents, often because they couldn’t be reached in time.

At the same time, officials announced a new requirement for law enforcement officers considering the arrest of a child younger than 12 to discuss with a supervisor other options. Preference must be given to the citation program.

While juvenile arrests have dropped in Hillsborough in the last five years, data show the arrest rate is still high compared to other counties, according to Dewey Caruthers, president of the Caruthers Institute, a St. Petersburg-based think tank that conducts studies on juvenile justice.

Hillsborough led the state in 2020 with nearly 400 juvenile arrests for first-time minor offenses, an arrest rate of 53 percent, according to Caruthers’ annual study, “Stepping Up: Florida’s Top Prearrest Diversion Efforts.” That number was roughly 15 times higher than Miami-Dade County and 50 times more than Pinellas County, according to the study.

“Florida would be a better place if every county handled common youth misbehavior like Pinellas and Miami-Dade counties,” Caruthers said when the study was released in January.

HOPE members reached similar conclusions in looking at the state data.

Jackson, the criminal justice co-chair, acknowledged that Pinellas and Miami-Dade counties do not have ineligible misdemeanor offenses like Hillsborough, but even accounting for that, the data still show that Hillsborough isn’t using the program to its full potential.

“As far as we can tell, the single most determinative factor is having that secondary look at whether the child is eligible for a civil citation,” Jackson said. “It’s that second set of eyes who can look at it more objectively after the fact.”

The Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office employs a juvenile civil citation coordinator who each morning reviews juvenile arrests, said Sheriff Bob Gualtieri. If the coordinator finds the offender meets the criteria for the arrest avoidance program, she’ll divert the case before it goes to the State Attorney’s Office.

Gualtieri didn’t have data showing how many cases the coordinator’s review diverts each year but said the process has a significant impact.

“Ultimately, if you don’t have a backstop, it’s totally within the deputy’s discretion and if a juvenile goes to the (Juvenile Assessment Center) and you don’t have anybody to catch it, that’s where it stays,” Gualtieri said. “There’s a whole bunch of kids who would otherwise be in the juvenile justice system if it wasn’t for this secondary review.”

Make citations mandatory?

Warren attended the HOPE event and said he “absolutely” would support and encourage the creation of such a review process. But Warren pointed out that “the key is in the hands of law enforcement” who make the arrests.

In written answers to questions from the Times, Warren said 156 arrests last year were referred to his office in situations where the children were eligible for civil citations. His office knows of 32 cases like that through February of this year.

“Those are kids who should be able a get second chance without an arrest hanging over their heads, but instead they’re now making the risky and costly journey into the justice system,” Warren said.

A secondary review process, he said, would keep more kids out of the system.

Asked if he would support other ways to expand the program, Warren said the county could offer citations to some second-time offenders, citing as an example cases involving low-level, non-violent offenses in which enough time has passed between the first and second offense.

Holt attended HOPE’s event last month and voiced support for a review process. But she told the Times the next step should be to eliminate the five ineligible misdemeanors and make the program mandatory for all first-time misdemeanor offenses.

“To distinguish between misdemeanor offenses just opens up the door for disproportionate treatment,” Holt said.

Holt said including misdemeanor domestic violence offenses in the program would help the county significantly reduce juvenile arrests.

“While it does appear to be a crime of force, we still have to remember it’s a misdemeanor offense and it’s important to educate a child about their actions rather than be punitive,” she said.

Warren stopped short of supporting a mandatory program, saying public safety is best protected by giving law enforcement some discretion. But to make the program more successful, he said, “we need to do a better job of documenting reasons why a citation was not issued.”

In written responses to the Times, Chronister said he is proud of the increased use of the juvenile citation program and said he doesn’t believe Caruthers’ study “accurately reflects our efforts at the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office.” But, the sheriff said, “there is still progress to be made.”

Chronister did not directly answer the question of where he stands on the secondary review process but said “we are currently considering a number of options that would enhance utilization for eligible low-level juvenile offenders.” He did not elaborate.

Asked if there are other strategies he would be open to exploring, Chronister said he welcomes ideas to increase the usage of the program, “which is why I routinely meet with organizations like the Hillsborough Organization for Progress and Equality, among others.”

Three days after the Nehemiah Action event, Chronister and Chief Deputy Donna Lusczynski met with Jackson to talk about the secondary review process. Jackson said the meeting was positive and that they agreed to revisit the issue in a month.

In an interview, Tampa police Chief Brian Dugan said he thinks the program works fine in its current form.

“I feel like in this particular situation they want to blame police instead of blaming the offender,” said Dugan, who also was invited to the Nehemiah Action event but said he was not able to attend. “I wish we focused more on programs to prevent crime as opposed to programs that are letting people off the hook when they commit a crime.”

VIew the original story here.