October 30, 2019. WFPL.ORG

For the first time, language in the operating manual for Louisville Metro Police Department’s professional standards unit will direct internal investigators to consider whether officers tried de-escalation as a way to avoid using force.

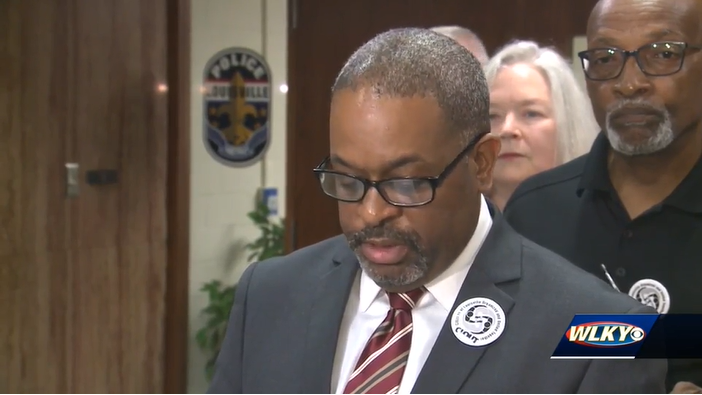

After months of discussion with city leadership, Citizens of Louisville Organized and United Together (CLOUT) is celebrating the proposed shift. Chief Steve Conrad announced the change Tuesday evening at a membership meeting hosted by the group.

Conrad said conversations with CLOUT “led to some changes that I think will not only improve our policies and our practices, but will hopefully also lead to a reduction in the number of injuries involving citizens and our officers.”

Chris Finzer, the chair of CLOUT’s mental health and addiction issue committee, said this new language doesn’t put new burdens on officers, but rather makes the potential for de-escalation more central to investigations.

Plus, he said LMPD is adding to its standard operating procedures information about interacting with people who may be intoxicated, suicidal or otherwise acting erratically. That will inform investigations into encounters with people who may suffer from mental illness or addiction, he said.

“It will definitely be an expectation for police officers to make greater use of the de-escalation tactics that they prescribe,” he said. “We believe that they will be expected to use them and if they don’t, the officers will be held accountable.”

CLOUT considers accountability to be lacking in this regard. Last year, the group announced it had reviewed 68 internal use of force investigations since adding its de-escalation policy, and CLOUT said it found that LMPD did not look at whether officers followed department policies for dealing with people with mental illness or addiction.

Mayor Greg Fischer met with CLOUT last year, but Finzer said the group wasn’t as successful as they would have liked to be in engaging him.

An LMPD spokeswoman confirmed the changes, but downplayed their significance. She said the new language simply makes explicit the expectation of using de-escalation when appropriate, which she said the department has already been trying to teach. She also pointed out that officers went through new training that included de-escalation techniques.

But Sam Walker, an expert in police accountability, disagreed.

“It’s a very big deal,” he said.

Walker is a professor emeritus of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. He said adopting a written policy of de-escalation isn’t enough. Police departments need to enforce it in training and discipline too.

“It’s become the standard across the country,” he said. “And I would say that Louisville is a little behind the times at this point.”

Departments traditionally didn’t offer guidance on these issues, which meant officers might have been less likely to try de-escalation, Walker said.

But, since the 2014 shooting of unarmed teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, many police departments have changed their approach. He thinks that more enforcement of de-escalation policies could lead to fewer instances of officers using force when it’s not necessary. And that could especially benefit groups such as African-Americans or those with mental illness.

The LMPD policy adjustments will go into effect on Nov. 7. Conrad said LMPD would track the effectiveness of its de-escalation policy changes and training, and announce results early next year.

View original article.