May 3, 2019. Naples Daily News.

Rain tapped lightly on the tin trailer as Amalia Mejia and her sister-in-law Bernabela Gonzalez forked tortillas from the skillet to the children’s plates for dinner.

“When I lived in company housing, we were four people to a room, unrelated adults,” Mejia said in Spanish. “In that kind of housing the crew leaders have keys and can come whenever they want.”

Mejia’s crew leader came often, harassing her with sexually aggressive behavior until she and her husband then found a rental – a tiny house behind the owner’s residence for $1,300 a month.

Although it’s more than half her family’s monthly earnings from farming, “I will never go back unless I have to,” the mother of three young children said.

Such conditions aren’t new in Florida’s largest farmworker community, but the situation has worsened since Hurricane Irma in 2017, according to Arol Buntzman, head of a nonprofit, Immokalee Fair Housing Alliance, which is trying to do something about it.

This room in a trailer in Immokalee offers occupants two bunk beds. It costs $70 a week for each person to lay their head on one of its pillows, according to the Immokalee Fair Housing Alliance. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

“Immokalee had very little decent housing to begin with, but Irma destroyed much of what was there,” Buntzman said.

Trailers have been a housing staple of low-wage earners and fixed income seniors, masking the absence of affordable brick and mortar solutions for them.

While Irma focused national attention on the lost trailers of Florida Keys hotel workers, farm workers had no leverage to fix the mold behind their soggy panels or holes that let in snakes and mice.

Bernabela Gonzalez serves freshly made tortillas for dinner in the trailer her family rents in Immokalee on Wednesday evening. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

“The owner only collects rent,” said Gonzalez, who with her husband pays over $1,000 a month for an old single-wide trailer. “If you call and say there’s a problem, he says, ‘If you want to fix it, fine. If you want to leave, that’s fine, too.’”

Even with a dedicated supply of public housing for farm workers, Collier County’s housing authority turned to its Lee County counterpart in 2016 to find more options for 1,200 families it couldn’t serve.ADVERTISING

The development called Farmworkers Village requires documentation to live there, which many don’t have.

So the Alliance, consisting of Peace River Presbytery, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and other concerned churches and nonprofits, is raising funds to build up to 144 apartments on 10 acres located at Lake Trafford Road and 19th Street, a block or two from the Winn-Dixie supermarket.

A trailer in Immokalee can cost more than $1,200 a month. Residents represented by the Immokalee Fair Housing Alliance describe mold behind the walls and invasions of mice, snakes and insects. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

The target cost of the apartments: $600 to $800 a month for a two- or three- bedroom, hurricane resistant unit; enough to cover real estate taxes, insurance and property maintenance, Buntzman said.

It’s a lofty goal considering other developers struggle to raise units costing twice that for people earning 80 percent of the area’s median household income. (In Collier, 80 percent would be $43,000. In Lee, it would be $35,000. The Mejias earn around $24,000.)

“One of the ways we can keep the rents low is to buy the land and build solely with donations and grants. not having to service a mortgage,” said Buntzman, a former serial entrepreneur and educator.

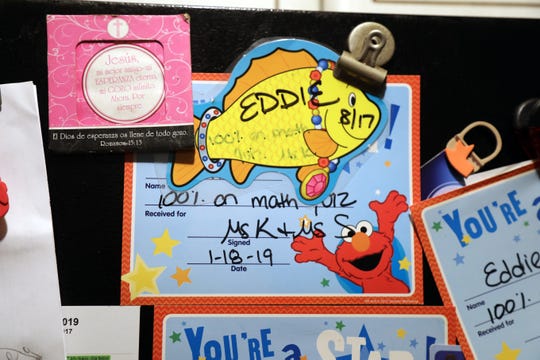

Ashely Gonzalez shows an attendance award she earned in school in Immokalee. Although she and her siblings live in crowded trailer conditions with no private space to study, she’s doing well in school. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

For example, “Knowing our purpose, Baron Collier Partnership agreed to sell the land to us at an affordable price. Kudos to them,” he said.

Besides the apartments, the plan calls for a community center with classrooms for early childhood education; a meeting hall; two laundromats; a soccer court and half-basketball court.

Collier County planners recently had their first look at the site plan by Andres Boral, whose Collier firmoffered its services pro bono. It shows 12 two-story buildings, each with 12 units. Depending on the environmental assessment, some land could be set aside to protect wetlands.

“They have a beautiful vision to give families better living conditions in permanent homes,” Boral said. “I believe it will help break the cycle of poverty.”

A different approach in Lee County

Across the county line, workers with job titles like cashier and retail sales have their own housing challenges, foraging for affordable rents on incomes similar to the Mejia and Gonzalez families.

Here Lee Interfaith for Empowerment recently gathered 900 people to ask Mayor Randy Henderson to create an affordable housing trust fund.

Those assembled heard stories like that of April Perkins who said she spends over half her income on rent, and Alison Carville, who can’t afford wheelchair-friendly housing on a disability check.

Children play word games before supper Wednesday evening at the trailer of Amalia Mejia in Immokalee. The Mejias pay $1,300 a month out of their $2,000 monthly earnings for the trailer, the reason so many live in over-crowded conditions. Living cheek to jowl, the children have no place of their own to study, but manage to do well in school. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

“We’re looking for the trust fund to create 3,000 more units over a five- to 10-year period for those at or below 80 percent of median income, just within the City of Fort Myers, organizer Chelsea Baker said.

Funds like this have committed some $2.5 billion to different kinds of affordable housing across the country, according to the Center for Community Change, which the interfaith group consulted to help form its ideas.

Amalia Mejia poses with her three children for a portrait in the trailer where she lived with her in-laws’ family and two other adults after Hurricane Irma . The house they previously rented was severed by a falling tree during the hurricane, and irreparably damaged. Another Mejia lived in, owned by a former employer, allowed supervisors to come and go freely, including one who tried to force himself on her. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

Unlike the Immokalee effort, however, the fund isn’t aspirational. Although it sets aside money for housing, what kind of housing is decided by the people and politicians involved, CCC Housing Trust Fund Director Michael Anderson explained.

“Florida’s Sadowsky fund was actually one of the most forward thinking,” Anderson said “Unfortunately Florida, given the ideological times, raided the fund and swept away $270 million a year.”

What would Lee County’s fund be used for?

“There are a lot of hurting people lower than that (80 percent of the AMI), The group that called me from Fort Myers shared this concern: ‘Affordable to who?'” he said.

Asked how much the trusts spend overall on housing for people who earn farm or cashier wages or live on disability and Social Security checks, Anderson said that data isn’t collected.

The refrigerator inside the trailer of Amalia Mejia in Immokalee is plastered with praises of the children’s performance at school. Although there is no place for them to study in the trailer’s crowded space, the kids are doing well in school, Mejia says. (Photo: Patricia Borns/The News-Press)

Asked for a guestimate, “Unfortunately over four decades we are at the greatest period of income inequality in our history, so there are arguments for middle class people to have affordable housing,” he said.

“What keeps me up at night is that the oxygen could get sucked out by this real need, although it’s not the most pressing or enduring one.”

View original article.