January 19, 2019. Lawrence Journal-World.

Ben MacConnell understands the dangers of attaching opinions on a modern issue to someone who can’t speak for himself, but he believes Martin Luther King Jr. would be a strong proponent of criminal justice reform.

“Given the billions of dollars we’re spending on jails and prisons, and the fact that more people of color are incarcerated than there were slaves at the height of slavery, he would be looking at this and, I think, want to spend a lot of time focused on it,” MacConnell said.

That’s one reason that the local grassroots coalition of faith communities for which MacConnell serves as lead organizer, Justice Matters, is planning to hold three simultaneous neighborhood discussions on restorative justice to commemorate the holiday celebrating King’s birthday.

Though it’s a complicated concept, MacConnell shared some basics of restorative justice. With the systems that are currently in place, if a person breaks a law or a child acts out in school, they are usually punished with jail time or suspension: “If you hurt me, how can I take something away from you or deprive you of something or sanction you in some way that would make the balance equal?” he said.

Restorative justice, on the other hand, wants to break that cycle. It aims to reconcile and repair the relationships and any harm that was done between victims and offenders. As a result, MacConnell said, recidivism declines and victim satisfaction improves.

“These are not unaccountable discussions — they’re highly charged, because the perpetrator isn’t just going to do time in isolation away from their victim,” he said. “They’re going to have to face what the victim is sharing about the crime, about the harm that they’ve committed.”

The concept does represent a major culture shift, MacConnell said, but it’s one that could gain traction locally.

The Lawrence school district has been exploring the concept. In November, it hosted several counselors and school principals for training called Implementing Restorative Practices in the Classroom, led by the Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (KIPCOR), district spokeswoman Julie Boyle said via email.

MacConnell said preventive measures could start with the schools — when kids are suspended, they become less likely to graduate and then more likely to be incarcerated in the future.

“So the school-to-prison pipeline is meant to be disrupted by trying to intervene, not with more punitive practices but restorative practices,” he said.

The discussions Justice Matters is planning for Monday will be interactive. Presenters will share a couple of case studies and may discuss a time that they’ve personally experienced harm in their lives, and then ask participants to recall a time when they’ve been harmed. Were they satisfied with the outcomes?

“In our research around the communities that are doing it well, it includes a significant amount of community buy-in — not just institutional buy-in at the criminal justice system or the school district, but you see people in the community who really support and understand what’s happening,” MacConnell said.

The discussions will be held from 6 to 7:30 p.m. Monday at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church, 5700 W. Sixth St.; Peace Mennonite Church, 615 Lincoln St.; and Ninth Street Missionary Baptist Church, 901 Tennessee St. The separate sessions aim to make it easier for people to share their experiences in smaller groups, MacConnell said.

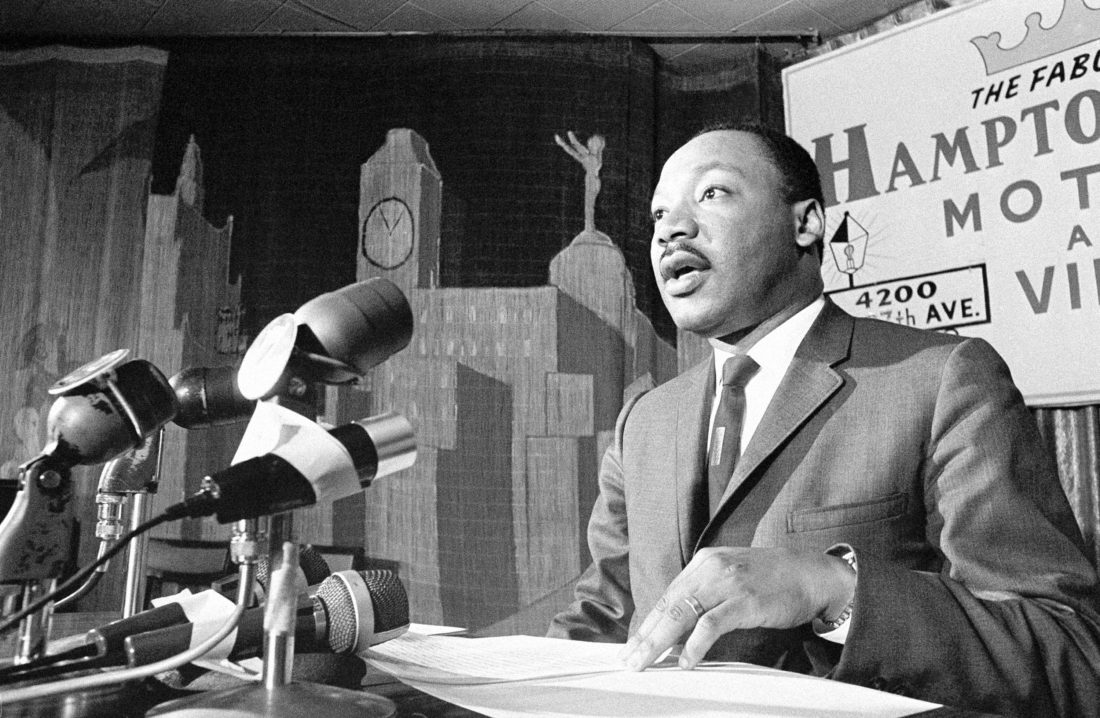

photo by: AP Photo/Charles E. Knoblock

In this AP photo from June 21, 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. addresses a crowd estimated at 70,000 at a civil rights rally in Chicagos Soldier Field, following congressional approval of civil rights legislation. (AP Photo/Charles E. Knoblock)

Today’s criminal justice issue is closely linked to the civil rights issues of King’s days, MacConnell said.

Though the “I Have a Dream” speech is likely King’s best-known work, MacConnell said it doesn’t capture the “radical prophet” and champion for social justice that King was.

“If you were to take that (speech) out of the canon of Martin Luther King writings and speeches, you would see a very strong-handed critic and an impatient man seeking desegregation, and then later the end of the Vietnam War, and then later, the end of poverty — and not in ‘kumbaya’ terms,” MacConnell said. “… He’s not apologizing for having what some consider strident views, and at the same time, a depth of love for even those who are fighting against him.”

He referenced King’s April 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and 1963 book, “Strength to Love” — perhaps better portrayals of the fighter who was willing to challenge the status quo.

“That book, for me, is a true indication that he would have adopted restorative justice as a theme in response to the gross number of people that are incarcerated in our country,” MacConnell said.

View original article.